The art of Lee U-fan encapsulates the oft-quoted axiom by architect

Mies van der Rohe that "less is more". A few rocks, sheets of steel and

barely painted white canvases make up Lee U-fan's powerful and evocative

exhibition at SCAI the Bathhouse. Using only these raw materials Lee U-fan

manages to create a serene beauty. And by careful placement of each element,

he creates a complex relationship between space and form. The paintings

and sculptures are engaged in a dialogue about space, form, color and

texture.

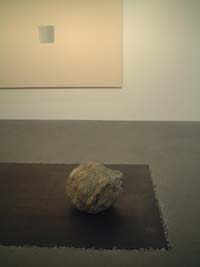

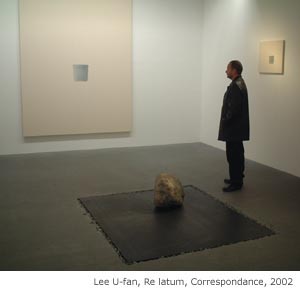

On entering the gallery, you are confronted with a large painting, which

is a reflection of the sculpture on the floor in front of it. The painting,

with two slabs of gray paint on a white canvas, is a reverse image of

the sculpture made of two large gray rocks on a sheet of dark steel. Throughout

the exhibition, the paintings on the wall echo the works on the floor

in a chorus of tones and tensions. In reference to this interaction within

his work, all of Lee's paintings are titled "Correspondance" (sic) and

his sculptures "Re latum".

Lee's paintings are as much about what is there, small slabs of gray paint,

as what is not –emptiness -- created by an immense expanse of white canvas.

Similarly, his sculptures activate the space around them, creating tensions

between the rocks, sheets of steel and the gallery space. Color, or perhaps

better described as an absence of it, is an important aspect of this exhibition.

Lee's new work is an oratorio of somber, monotones of gray.

At the center of the exhibition is a sculpture, which expresses the forces

of gravity. A steel plate has been embedded into the concrete gallery

floor. It appears to have just crashed there from above. The steel plate's

top surface is at the same level as the floor into which it is recessed

and is surrounded by the cracked chunks of broken concrete. These jagged

cement pieces form a sort of rock garden frame around the steel.

Lee u-fan, born in Korea in 1936, was a founding member of the seminal

Japanese art movement of the late sixties called Mono-ha (School of Things).

This radical group was active politically, artistically and culturally.

Lee, in particular, was determined to work towards an art that was contemporary

and relevant, yet uniquely Asian in its vision. Throughout his artistic

career, Lee has looked towards the traditions of Zen Buddhism to achieve

this Asian dimension in his work.

Lee's work is plain simple. It tinkers between being nothing more than

a few random rocks and ethereal aesthetic enlightenment. And like all

profoundly simple statements, it is easy to mock, while requiring considerable

effort to appreciate. The work of Lee U-fan exists at the edge of art,

on the horizon between the natural world and the spiritual.