From beach sand to computer chips, Silicon is one of the world's most extraordinary elements. It is, after Oxygen, the most abundant element on the earth. Silicon forms the basis for both clay and glaze. Very early in human development, Asia became the center for invention and innovation in ceramics in the world. The Chinese, Koreans and then Japanese became the masters of the medium. An exhibition at the Suntory Museum of Art explores ' 1200 years of Japanese Pottery: from Nara Sansai, Imari and Nabeshima ware through Ninsei and Kenzan.'

On display are several designated cultural treasures. Among them is an Edo Period (18th century) Imari bowl decorated with five sailing ships and Europeans. The painted decorations are in five colored glazes as well as gold. The piece is a masterful example of ornate decoration as well as a document of Japan's contact with European traders.

The making and firing pottery is a complex process open to unpredictable variations. Ceramic artists have always been open to the beauty of accidents and imperfections in their artform. Early in the exhibition is a series of large storage jars. These simple utilitarian objects display through their lumpy form their hand built origins. They display the colors and variations of their fiery birth in the pottery kiln. Pure abstract design in pottery preceded that of painting by many centuries.

Included in the exhibition is a large sake bottle of Nabeshima ware, which is decorated with a splatter of cobalt blue. Although created in the 17th century it is as dramatic as anything that Jackson Pollack threw onto a canvas. Similarly 'modern' in appearance is a plate, circa 160-1730, decorated in a radiating floral pattern. The design explodes across its surface like fireworks.

A bowl by Nonomura Ninsei, a 17th century pottery designer, is dented on one edge and folded in on itself. It is almost unglazed apart from a dollop of dark brown on the folded edge. A pattern of circles is formed on the bowl from where other pots were stacked upon it during firing. It is a simple, dramatic, abstract form. The bowl captures the purity and simplicity of Zen.

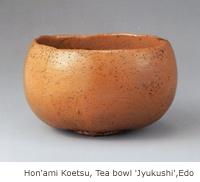

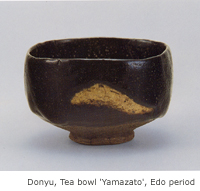

With connections to Buddhism and the tea ceremony, ceramics is one Japan's cultural foundations. A small group of tea bowls is the highlight of this exhibition. Of these, two examples of Raku pottery stand out for their rugged natural form and simplicity. A black bowl, by Donyu, is from the Edo period (early 17th century). It was hand formed round in shape but was then pushed square before drying. The dark glaze is broken by a slice of lighter clay depicting a mountain, Yamazato, after which the bowl has become known. On display next to it is an example of red raku ware by Hon'ami Koetsu, better known as a designer and critic from the same period. His tea bowl resembles the persimmon fruit in both color and form.

The Suntory Museum exhibition is elegantly displayed. Although an English list of works is available on entry, unfortunately, none of the extensive label information, wall text, or catalogue is in English. Nonetheless, this highly recommended exhibition offers a comprehensive survey of Japanese pottery over many centuries. It is also an opportunity to see some rare examples of the country's most treasured ceramic artifacts.